One in a series of Uncomfortable Topics.

A sermon by Rev. Leland Bond-Upson, Unitarian Unitarian Church of Vancouver, December 13, 2015.

© Leland Bond-Upson. Please request permission to quote. Leland@lovingbond.org/lbuuu

Click the image for an audio recording of this sermon.

Click your browser back arrow to return to this transcript page.

There is nothing new under the sun. That includes an abiding human nature. Social class distinctions are as old as human community. We cannot hope to change human nature, but like other human passions and sins, we can hope to tame it, through community.

I wish to say at the outset that I don’t really mean to make anyone uncomfortable this morning. I simply wish to talk about the reality—I think we can say it’s a reality—of perceptions of social class. So please bear with me, in the faith that I mean well—and may have relief in store at the end.

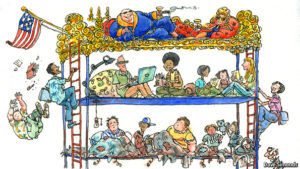

Social class in America can be divided up in several ways. For a century or more, it was like in England: simply Upper, Middle, and Lower classes. In the 20th Century, ‘lower class’ became ‘working class,’ due in large part in recognition of Labor’s rise.

In the 19th C., Matthew Arnold used the same three classes, but renamed the Uppers “the Barbarians,” the Middle “the Philistines,” and the Lowers “the Populace.”

Americans love seeing class distinctions writ large and clear in representations of the English class system. Downton Abbey is only the most recent. Before that there was Howard’s End and all the E.M. Forster stories, and the Forsyte Saga, and Gosford Park, and all the Jane Austen stories, and Brideshead Revisited, and what could be more class-conscious than Upstairs, Downstairs?

The English gobble up this stuff too. Why do so many of us find this stark portrayal of class so interesting, and so pleasurable? Perhaps because part of us is comfortable with limits.

In America, we too, for a long time had Upper, Middle, and Lower. Some American sociologists felt that more than three divisions were needed, and came up with: Upper, Upper middle, Middle, Lower middle, and Lower.

Lower-middle in those days meant a person, a man usually, who had a solid high school education, and had gone into skilled manual labor. Not a miner, for instance, but a master carpenter. In the 2nd half of the 20th C. “Lower class” was squeezed out of existence and replaced by the high end of the Proletarian class.

This last division has lasted 30 years, and was worked out by a writer named Paul Fussell, in his 1983 work, Class, a Guide Through the American Status System. A lot of people know or have heard about at least part of his nine classes, which are:

First, the three upper classes:

• Top out of sight, the 1%ers;

• Upper Class (Richard Branson plays games with us by allowing us to book a seat in Virgin Atlantic’s “upper class” cabin.)

• And upper middle (btw, seen from above, by the top two, upper middle class isn’t Upper Class at all. Seen from below, it can look pretty upper.)

Then, the four solidly middle classes

• Middle

• High Proletarian

• Mid-Proletarian

• Low Proletarian

The proletarian classes are still known as working class, but also known by the derogatory term ‘prole.’

And finally, the two lowest classes:

• Destitute (the poverty-stricken, including homeless, and bag-ladies, and hobos, although hobos have an odd little class of their own, a special society, with a code of conduct: Gentlemen of the Road)

• Bottom out of sight (the institutionalized, in prison, in mental hospitals, or in hiding, in a welfare hotel room, or a shack outside of town).

When I preach on Race, I speak of how it’s an unfortunate part of human nature to want to elevate oneself by looking down on others. Classism is another way to look down on others. It’s a little bit fun, but at bottom, it’s not nice. It’s an uncomfortable subject to talk about.

I was raised in the upper half of Middle class, whereas my wife was raised in the middle third of the Upper Middle class.

While I’m on the subject, I confess that I was eager to leave the middle class, and lapped up Upper-ish class knowledge and taste. I wanted to learn that the one pronounces the 16th C. Italian painter “tish-un” and not something else, something wrong. I wanted to learn about Ezra Pound, and Swedenborgianism, and the difference between silver plate and sterling, and how a lithograph differs from offset press reproduction. I wanted to know the difference between Corian and limestone and granite. I wanted to know the difference between pine and fir, and the hardwoods, and fruitwoods.

Like Hindu India, we have caste here too, although they are not written into our law. There are thousands of things that are called ‘caste markers.’ If America were to start thinking in terms of caste, it would be helpful in conveying the rigidity of class here, “the difficulty,” Fussell writes, “of moving—either upward or downward—out of the place where you were nurtured.”

It’s important early on to make a distinction between wealth and class. Wealth plays a role, but not an exclusive one. We find “classy people” in all classes—even, as I learned as a social worker in San Francisco—even among the destitute and bottom out of sight.

One’s class is also a factor of one’s education, intelligence, awareness, refinement, true courtesy, true kindness, true generosity, true gentleness.

Donald Trump has a lot of money, but nobody who has observed him would call him ‘classy.’ He has said in interviews that he’s not comfortable with rich people. He’s much more comfortable with ‘ordinary people,’ he says. Well no wonder. His wealth allows him to be his vulgar, dishonest, bullying self and not be called on it. I imagine he doesn’t like upper class people because they, in their relaxed confidence, and acute eye for class markers, see him for what he is.

In Brave New World, Aldous Huxley created a future society that is heavily regulated. Re-reading it, I caught a whiff of where China may be going.

You may recall the castes in this brave new world. They ran from Alpha++ down through Beta, Gamma, Delta, to Epsilon, the lowest. Children were manufactured biologically, and raised with class-appropriate educations—and mindsets. There were lots of people in the lower castes to do the work, and fewer as the caste pyramid narrowed toward the top.

I decided I wanted to be an Alpha+. Alpha++s were the theoretical physicists and mathematicians. Alpha+s were more like old-time aristocracy; they had more freedom and more fun. But in fact, this new world is air-tight totalitarian, and nobody has much more than the illusion of freedom. Huxley was describing a world where class meant everything, and was assigned. He was saying, of course, that our old world was not so very different from his dystopian new one.

We are immersed in class distinctions and judgments—or should we say, condemnations. Some we are acutely aware of, some we sense, uneasily, some we embrace, some are unconscious—they’re in our DNA, in our breeding.

Here are the main categories of markers:

How you speak

How you write

How you dress

Where you live

What your house is like

What your yard is like

What your living room is like

Whether or not you have books,

And if you do, what kind of books.

What kind of magazine do you have out,

and might you be trying to make a statement with them?

[I confess I did, and fairly recently. It’s a sign of my middle class origins and insecurity that I care what people might think about what I’m reading. The securest classes don’t give a hoot about what people might think.]

What kind of dog you have, and is it pure-bred? –or for UU’s, is it a rescue dog?

What’s in your kitchen and bathroom

What kind of car do you drive?

Is the Formica in your house an honest, solid color, or is it pretending to be something else?

Do you have horses, and if so, do you use them to look down on people?

What do you drink, and what kind of glasses do you have?

How much of your diet is sweets, carbohydrates, fried food, fast food?

Do you live in a place that is associated with religious fundamentalism (like Greenville, SC (Bob Jones), Lynchburg, VA (Jerry Falwell), Garden Grove (Rbt Shuller), or Tulsa (Oral Roberts). One can be a wonderful person and come from such a place, but you will have trouble getting accepted as part of the upper classes.

Does your town have a respectable daily newspaper? (Oh dear.)

And on and on. Everything is steeped in class-consciousness, or unconsciousness.

Enough. The middle class, Fussell says, is the most tortured about class issues and appearances. It’s hoping to move up, worried about slipping down, it is always in a state of anxiety and uncertainty.

Only the very rich, in their confident, carefree, careless way can ignore all this. The very poor don’t have the time and can’t do anything about it. Everyone else is worried, or has checked out in one way or another.

[Add here: Auntie Biff’s wrecking of mother Bertha’s plan for her]

There is a better way to deal with this than defiance or despair. There is a way out.

Mr. Fussell, in his Class in America, has a 10th class, which he calls Category X. This has nothing to do with Generation X. As it turns out, it well suits us, as it does any free people. I quote from Fussell, who is enamored with the X-class, or non-class.

“X people are better conceived as belonging to a category than a class, because you are not born an X person, as you are born and reared to be Proletarian or a Middle. You become an X person, or [rather] you earn X-personhood by a strenuous effort of discovery in which curiosity and originality are indispensable. And in discovering that you can become an X person you find the only escape from class. Entering category X often requires flight from parents and forebears. The young flocking to the cities to devote themselves to art, writing, creative work—anything, virtually, that liberates them from the presence of a boss or supervisor—are aspirant X people, and if they succeed in capitalizing on their talents, they may end as fully fledged X types.

“What kind of people are [these]? The old-fashioned term bohemian gives some idea. Some Xs are intellectuals, but a lot are not: they are actors, musicians, artists, sports [professionals] well-to-do former hippies, and [journalists]. They are ‘self-cultivated.’ They favor self-employment, doing what social scientists call autonomous work. If the middle class person is “always somebody’s man,” the X person strives to be nobody’s, and her freedom from supervision, if she can achieve it, is one of her most obvious characteristics.

“X people are independent-minded, free of anxious regard for popular shibboleths, loose in carriage and demeanor. They try to find work they adore, and if they do, they do it until they are finally carried out. ‘Retirement’ [to them] is a foreign concept. Being an X person is like having much of the freedom and some of the power of a top-out-of-sight or upper-class person, but without the money. X category is a sort of un-moneyed aristocracy.”

“X people tend to dress down a notch. If the Xs ever descend to wearing ‘legible clothing,’ the words—unlike “U.S.A. Drinking Team”—are original and interesting, although no comment on them is ever expected. When an X person meets a member of an identifiable class, the X-costume, no matter what it is, conveys the message “I am freer and less terrified than most.” The clothes worn are not advertising for some company, but proclaim oneself, one’s individuality, and independence.

X people change location when they, not their bosses, feel they should. Their houses are more likely to be old than new; old ones are cheaper, for one thing, and by flaunting a well-used house you can proclaim your freedom from the American obsession with the shiny up-to-date.

Many X people are more likely to take back roads or the old U.S. Highway system roads rather than the boring, soulless Interstates. Charles Kuralt, who reported for CBS News for years, and had a wonderful show called Charles Kuralt On the Road. He said that ‘you can cross the whole country on the Interstate and not meet anyone.” May I suggest, on your return from say, Eugene, give yourself an extra half hour or more, and take 99W through Junction City, and Monroe, and Corvallis, and Monmouth, and Rickreal. And don’t drive, motor. Those older highways follow the contours of the land, and you get to look down and see the Willamette Valley in a way you have perhaps forgotten. It’s much better for the soul.

“X people tend to be loose about mealtimes, hunger and convenience being their only motivations for eating. Like the uppers, Xs generally eat late rather than early, and their meals often last longer, what with all the prolonged comic and scandalous narrative at the table. X people don’t eat dinner out much. Intelligent and perceptive as they are, they know that if you’re at all clever, you can eat better at home. They also get no satisfaction from bossing waitresses around as an outlet for what they’ve endured from their bosses earlier that day.

“Xs are fairly free with the four letter words, but use them judiciously in comic or ironic ways, and not in anger. Xs hate euphemisms, which they see as the realm of the middle class. They use ‘lover’ instead of constant companion, and ‘death’ instead of ‘passing away,’ or ‘crossing over.’

In most every aspect of life, the X-person chooses freedom, and refinement, and liberality.

X people constitute a classless class. They resemble E.M. Forster’s “aristocracy of the sensitive, the considerate, and the plucky.” They occupy the one social place in the USA where the ethic of buying and selling is not all-powerful. People fearful that X-hood may be somehow un-American would do well to remember that Mark Twain created an exemplary X-person, and said, when first introducing him, “Huckleberry came and went, at his own free will.”

For all the people who aspire to get into the upper-middle class, there are a constant few with notable gifts of mind and perception who aspire to disencumber themselves into X people. It’s only as an X, detached from the constraints and anxieties of the whole class racket, that an American can enjoy something like the LIBERTY promised on the coinage. And it’s in the X world, if anywhere, that an American can avoid some of the envy and ambition that pervert so many lives.

The society of Xs is not large at the moment. It takes a kind of moral courage to stand apart from what so many others consider normal, and proper. X-Society could easily be larger, for many can join who’ve not yet understood that they have received an invitation, from the examples of the lives of those who have at least partly freed themselves from the tyranny of class. That’s what we can do for ourselves, and I hope everyone in the world will opt out of the class system.

We must keep in mind though, that being able to opt out is part of our class privilege, which in America and the West is part of white privilege. One of the worst aspects of the New Jim Crow is the forced reassignment, through mass incarceration, of millions into the growing Bottom-Out-of-Sight class, from which opting out to X-class is a ludicrous proposition.

David Brooks, a moderate and classy conservative who writes for the NYTimes, pointed out a year ago in an opinion piece titled “Class Prejudice Resurgent,” that “widening class distances produce class prejudice, classism. . . a view which metastasizes into vicious, intellectually lazy stereotypes. Class prejudice is applied to both the white and the black poor, whose demographic traits are converging. Ultimately, Brooks says, we don’t so much need a national conversation [on race and class], we need a common project. If the nation works together, he writes, to improve social mobility for the poor of all races, through projects like President Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper initiative, then social distance will decline, classism will decline, and racial prejudice will obliquely decline as well.

In a friendship, Brooks concludes, people don’t sit around talking about their friendship. They do things together. Through common endeavor people overcome difference to become friends.

That common endeavor idea has worked in other places, like in families, in team sports, in business. There is reason to believe common endeavor might overcome differences within churches, too. [END]

I have a few copies of a class self-evaluation called “The Living-room Scale.” I can give these few away during sermon discussion. At the very least it will make you self-conscious, and could be upsetting, so consider not taking it.